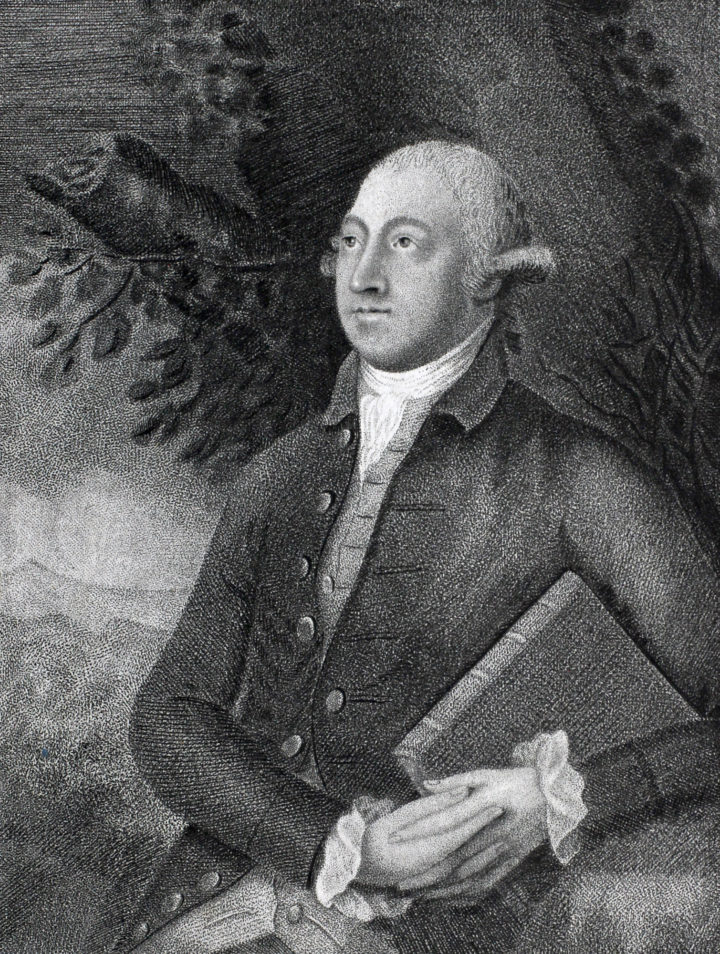

Thomas Pennant – naturalist, traveller and letter-writer

Published on 23rd November 2018

Last week the Linnean Society hosted a conference marking the end of ‘Curious Travellers’. This four-year research project looked at how the pioneering travel writings of Thomas Pennant (1726-1798) inspired a new public interest in the ‘peripheries’ of Britain.

Although his name is not so well known today, in his time Pennant was an acclaimed naturalist, antiquarian and writer. Charles Darwin owned a copy of Pennant’s History of Quadrupeds and had it sent to him in South America during his Beagle voyage.

Pennant corresponded with a wide international network of leading scientific figures, including Carl Linnaeus, on whose collections our Society is founded. This correspondence survives in our archives today and reveals not only Pennant’s passion and curiosity for the natural world, but also an energetic personality not averse to a little gossip. He often flatters Linnaeus and, in 1771, surely aware of the growing rift between him and his former student, Daniel Solander, Pennant alludes to Solander’s failure to send Linnaeus promised specimens:

‘a liberal and communicative disposition is the highest honour to a man of science’.

One of Pennant's letters to Linnaeus

A year later, Pennant laments that

‘Joseph Banks has conceived a jealousy of every old friend he had; and is quite averse to encourage merit in others; so I suppose Solander has followed his example’.

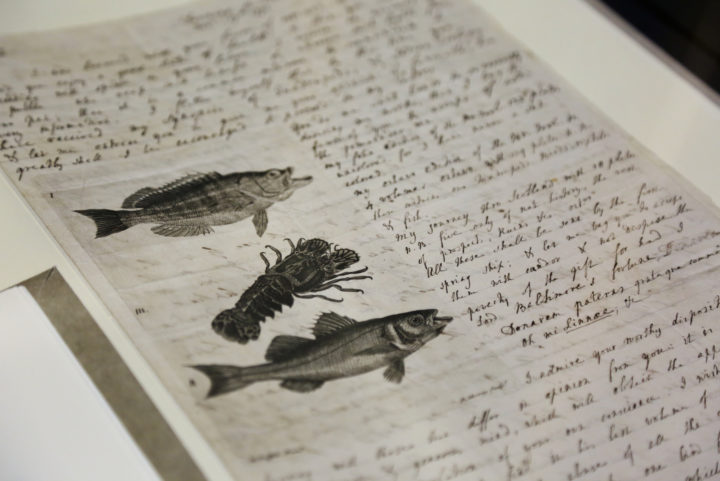

Another letter sent to Linnaeus from Pennant, showing some striking illustrations

After Linnaeus’ death, Pennant began writing to James Edward Smith, who had bought Linnaeus’ collections and founded the Linnean Society. In these letters, Pennant’s tone is respectful but also shorter, very much that of an older man talking to his junior. He declines to become an elected member of the Society three times, citing his advanced years, and later resigns the Honorary Membership he has been given, furious that he feels the Society has admonished him for profiting from his publications.

Pennant corresponded with Smith right up until his death, and even throughout the clashes mentioned above remained curious and engaged with questions about the natural world.

A quote from a 1793 letter to Smith captures both Pennant’s devotion to science and spry attitude perfectly:

‘Men of science never need apologize for the revival of trouble respecting information, nor do any delay it, unless the little fat curator of the British Museum.’

Pennant’s beautifully illustrated publications and correspondence are an important part of our research collections. Explore our catalogues to find out more! https://www.linnean.org/research-collections

By Dorothy Fouracre, Librarian