Collinson’s Connections: The Commonplace Book of Peter Collinson

Assistant Archivist Luke Thorne writes about his work cataloguing the "commonplace books" of 18th-century botanist, Peter Collinson

Published on 14th June 2020

Although he was a cloth merchant by trade, Peter Collinson (1694-1768) had an immense passion for the natural world and scientific enquiry. He was a keen gardener who devoted much of his life to developing his understanding of botany and encouraged others to get involved in enhancing their own gardens with exotic plants. Furthermore, he used his influence as a trader to create a network of connections with many famed botanists and scientists including Carl Linnaeus, John Bartram, Mark Catesby and Benjamin Franklin. These connections became lasting friendships in which Collinson offered financial support, or promoted their work in his position as a Fellow of the Royal Society. In exchange he received seeds, plants and trees from other parts of the world and introduced them into English gardens, including his own in Mill Hill, which became a school in 1807 and maintains a heritage garden in honour of Collinson today.

In establishing and maintaining these connections, Collinson has left us with a paper trail of his activities and interests, which he compiled in his commonplace books. Commonplace books have been used since antiquity as compendiums of knowledge collected by an individual and served as an information resource. The Linnean Society of London holds within its archive two boxes containing the unbound pages from Peter Collinson’s commonplace books, which feature an assortment of letters, notes, observations, biographical accounts, diary entries and scientific papers.

"Adieu, live long and happy": Carl Linnaeus' words to Peter Collinson in a translated letter (MS/323a/11-14)

A third commonplace book belonging to Peter Collinson also exists, but is not part of the Society’s holdings. At the time of writing, an export bar has been placed on it along with two volumes of Mark Catesby’s The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, which were owned by Collinson. This particular commonplace book contains original 18th-century drawings and prints of plants, birds and animals, which were made by Mark Catesby, William Bartram, Georg Ehret, and George Edwards. The bar has been placed on the books by Arts Minister Helen Whately to prevent them from leaving UK in the hopes that a buyer will step forward to purchase these drawings. They have been valued at £2.5 million.

As the Assistant Archivist, it has been my responsibility to accurately describe the contents of the commonplace books in our care, and provide contextual information about Collinson and his writings. This project, which has involved the study of paleography, transcription, and historical research, has culminated in this article and the successful inclusion of the commonplace books in the Linnean Society’s online archives catalogue (at reference numbers MS/323a and MS/323b). We hope that our users will enjoy the addition of new collections to our catalogue as a means to further their research.

While much of the books’ contents were written by Collinson, he also included many letters, papers and other documents he received from friends and acquaintances. It is of no surprise to find letters from ship captains and scientists about deliveries of tables, maps, seeds and other specimens that he received as well as general letters informing Collinson about the activities and wellbeing of those he was in contact with. However, Collinson also kept and recorded notes on areas related to history, geography, astronomy, literature and architecture. Essentially the book is a testament to the connections and relationships Collinson developed throughout his life, and his pursuits not only into botany and scientific enquiry, but a wide variety of subject areas.

"... the book is a testament to the connections and relationships Collinson developed throughout his life..."

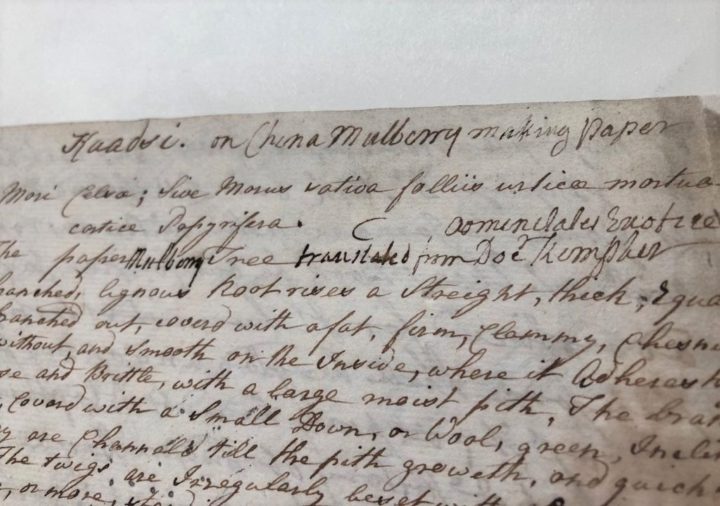

Scientific notes and papers are a prominent feature in the book, which were sent to Collinson to be promoted by him at the Royal Society. The varied topics of the papers that Collinson kept in his commonplace book suggest that his personal interest in scientific enquiry went beyond the subject of botany. The book contains papers describing the process for making paper papyrus from Chinese Mulberry trees, the resistance between solids and liquids in relation to the structure of ships, and the cause of thunder written by Edward Wright. Collinson also showed a great interest in and support for Benjamin Franklin’s experiments with electricity, and was instrumental in Franklin’s admission into the Royal Society in 1756.

Varied interests: Collinson's commonplace books touch on a plethora of subjects. This portion of text describes the use of the Chinese mulberry (Morus australis) in paper-making (MS/323a/23-26).

Another subject of interest that frequently appears in the book is North America, as Collinson and his brother James had established trading relations in the continent for their business, which led to Collinson making contact with American botanists and scientists. The city of Philadelphia was of great significance to Collinson as he was a patron of the scientific community there and made a donation to the public school of Philadelphia in 1749. A full catalogue of the books donated, consisting of 193 books and 11 pamphlets, is included in the commonplace book as well as a grateful response from the school’s officials.

International connections: an official in Philadelphia thanks his "esteemed friend" Collinson, in a handsome copperplate hand, for a donation of books and papers to the public school of Philadelphia in 1749 (MS/323a/47-52)

Of course, there are also many descriptions and notes on American flora and fauna, including deer, elk and birds. Collinson used his trading networks to gather scientific information as well as specimens. His networks had close links with indigenous populations, who played an important role in the transmission of knowledge of natural history. Sections of the commonplace book reveal the ways in which Collinson and his correspondents interacted with and viewed Native American populations, from descriptions of the food they ate, to grisly accounts of cannibalism and ‘murders committed by the Indians in Carolina’, but also proposals for peace.

"[Collinson's] networks had close links with indigenous populations, who played an important role in the transmission of knowledge of natural history..."

Remarkably, the book also contains copies of historical documents that Collinson recorded himself. One example is a copy of a handwritten order made by Queen Elizabeth I in which she grants custody of some of her possessions to several individuals. There is also an extract from the letters of the Roman writer and statesman Seneca the Younger about physical health and how he became more considerate for his own wellbeing after his wife urged him to take better care of his health (Seneca, Moral Letters to Lucilius, 104.1-5). Unfortunately there is no indication given by Collinson on why he chose to make copies of these particular texts, but for whatever reason he chose to have them as part of his book.

Transcribing a transcriber: an extract from Collinson's copy of a handwritten order made by Queen Elizabeth I (MS/323a/87-88)

Collinson’s love of planting and efforts to enhance English Gardens throughout his life are also reflected in his book through descriptions, comments and instructions on gardening. Many of the instructions in the commonplace book relate to planting seeds he received from America and detailing how to cultivate their growth as well as how to properly prune them. He also provided his comments on plans for a rural garden as well as garden plans made by Lord Petre, and drew up a design for a greenhouse, which includes details of measurements, materials and accommodations for shutters to be placed on the building to provide light and heat control during different times of year.

Ingenious gardener: Collinson's drawing of a greenhouse, with labels and measurements (MS/323a/97-100)

Ultimately, Peter Collinson’s commonplace book is a very personal object and offers us some fascinating insights into his life and the passions he had. What really shines through in these pages is the sense of exploration and drive to discover more about the world he lived in, which is something we can all learn from.

By Luke Thorne, Assistant Archivist

All images © The Linnean Society of London.

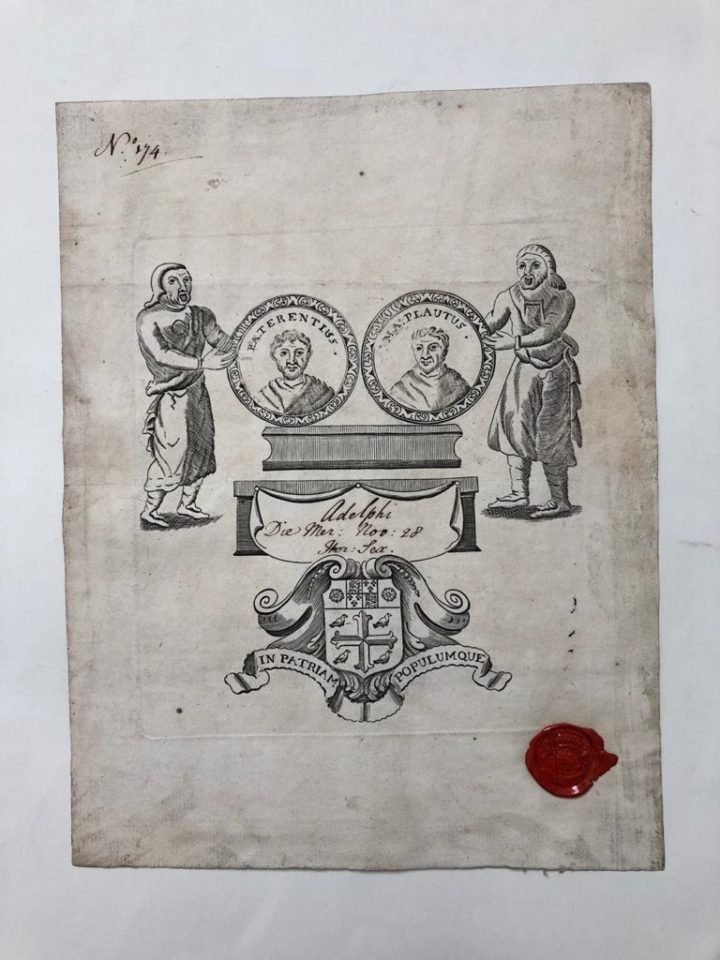

Bookplate at the front of the first commonplace book (MS/323a)

Engraving of Collinson in middle age, from the Society's portrait collection (EP/C/59)