"Before Fellowship": Celebrating Women in Natural History at the Linnean Society

This International Women's Day, we celebrate some of our scientific champions—suggested by our staff and members—from the years before 1905

Published on 4th March 2022

In March 2020, we mounted a portrait exhibition in our library celebrating the first cohort of women admitted to Fellowship of the Linnean Society in 1905. Their admission came as part of a long struggle for recognition and equality in the face of widespread prejudice, indifference, and open hostility. It was a remarkable achievement.

But the history of women at the Linnean Society, and in the study of natural history more generally, does not begin and end in 1905. What of the women natural historians who worked—often unsung, unpaid, and uncredited—in the centuries before this watershed moment?

As we celebrate International Women's Day, we're pleased to present a selection of our own scientific champions—suggested by our staff and members—from the years before Fellowship; women whose work helped change both our Society and our discipline.

It's a partial list—as all such selections are—and an eclectic one. Some names are justly famous; others, unjustly forgotten. Still, as we take a tour through the past, and learn about these women and their incredible achievements, we hope there will come an opportunity to reflect on the progress we've made, and the work that remains to be done.

Maria Sybilla Merian (1647–1717)

EP-M-37: Engraved Portrait of Maria Sybilla Merian

The German-born naturalist and illustrator Maria Sybilla Merian is a hero to many modern scientists, praised both for her personal bravery and her scientific and artistic gifts. She's best known today for her intrepid, self-funded expedition to Suriname in South America between 1699 and 1701, in which she produced the groundwork for her monumental Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium (1705).

Aside from its artistic accomplishment, Merian's work has scientific value because she was among the first naturalists to draw insects in the field, and at each stage of their life cycle. This set her apart from prior artist-naturalists, such as Conrad Gessner, who usually worked from preserved samples.

Prunus Americana, from Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium (1705)

Merian was also at pains to record the names and uses accorded to insects and plants by the indigenous peoples of Suriname, giving her dissertation added value as an anthropological document of the region at the height of the colonial period.

One of the greatest testaments to Merian's enduring legacy can be found in the pages of Carl Linnaeus' own works. Turning to entries for South American plants and animal species, Linnaeus again and again cites his source, "Mer."; Merian's laconic abbreviation.

The Linnean Society is fortunate to possess Merian’s Dissertation in two editions: one coloured from 1719, and another uncoloured from 1726. They are stalwarts of our rare books classes, and among our library's most beautiful and charismatic items.

Susanna Lister (c.1670–1738) and Anne Lister (1671–1700)

Only in recent years have the Lister Sisters, Susanna and Anne, been justly recognised among the preeminent natural history illustrators of the 17th century. Trained by their father, the physician and "father of British conchology" Martin Lister, Susanna and Anne supplied meticulous illustrations of shells for their father's works, and for issues of the Royal Society's Philosophical Transactions. Anne's work for the latter has led some historians to speculate she may have been the first female illustrator to use a microscope for science.

Conus marmoreus from Historiae Conchyliorum by Martin Lister, engraved by Anne Lister

The Listers came too early for the founding of the Linnean Society, but their fingerprints are everywhere in our collections. Their work appears to have been especially prized by our pater familias, Carl Linnaeus himself. No fewer than six works by the Listers are preserved in his library; only his own works, and the works of a few key botanists, are more generously represented.

In 2017/2018, we were privileged to assist Prof. Anna Marie Roos in her research for what has become an essential study of Lister and his industrious family. Martin Lister and his Remarkable Daughters was published by the Bodleian Library press in 2019, and a copy is available in our library.

Elizabeth Blackwell (1707–1758)

Lithograph portrait of Elizabeth Blackwell (c.1700–1758)

If ever a woman was undone by an unreliable man, it was Elizabeth Blackwell. Born in Aberdeen around 1707 to a well-heeled mercantile family, Elizabeth secretly married her cousin Alexander Blackwell in 1728. A shady character of doubtful honesty, Alexander’s double-dealing would indirectly lead to the production of Elizabeth’s masterwork. After a scandal involving Alexander's medical qualifications, the couple hastily relocated to London, where Alexander quickly established himself as a jobbing printer. Unfortunately, not unlike medicine, the business of printing was a protected profession—with a compulsory apprenticeship—and when the printers’ guilds questioned Alexander’s credentials he was swiftly and harshly fined.

Unable to pay, Alexander was condemned to a debtors’ prison, leaving Elizabeth and their first child to fend for themselves. Determined to save her family from penury, Elizabeth capitalised on the artistic refinements she had acquired as a young girl in order to create a fashionable and lucrative herbal, with a focus on the “curious” exotic plants emerging from East Asia and South America. With the help of Isaac Rand, curator at the Chelsea Physic Garden, and with text supplied and corrected from her husband’s cell, Elizabeth gradually built up a two-volume work of some 500 images, with each weekly instalment containing four pages of italic text to a single leaf of copperplate engravings.

Engraved plate 54 from Elizabeth Blackwell's Curious Herbal (1739)

Sadly the outcome for Elizabeth and Alexander was not so happy. Through her industry and perseverance, Elizabeth was able to secure her husband’s release from prison, but the reprieve was only temporary, and he soon fell into further difficulties. In 1742, with creditors knocking, Alexander abandoned the family altogether for Sweden. While there he managed to acquire the improbable position of court physician to Frederick I, an appointment that should have secured his fortune. But ever a magnet for trouble, Alexander embroiled himself in a courtly intrigue involving the line of succession, and was executed for conspiracy in 1748.

Elizabeth's life was not an easy one, but the work she created—her Curious Herbal—is a masterpiece of botanical illustration, a jewel of the Linnean Society's rare books collection, and a testament to her creativity and determination. If you would like to learn more about Elizabeth Blackwell and her work, you can read the full Treasure of the Month article from July 2021 (of which this potted biography is an abridgement).

Anna Atkins (1799–1871)

Anna Atkins, photographed in 1861

Among the many technical innovations of the 19th century came a new method of depicting the natural world. Photography is now an omnipresent part of our lives, and the role of John Herschel and Henry Fox Talbot in its development is widely celebrated. Less well-known is the contribution of one woman from Kent, the creator of what is considered the world's first book of photographs.

Anna Atkins was the only daughter of the prominent scientist George Children, a member of the Royal Society and an early correspondent of Herschel and Talbot. She was a gifted scientific illustrator, producing several beautiful engravings of shells and other subjects, mostly for her father's publications.

The Linnean Society's set of Atkins' three-volume, Cyanotype Impressions

Her greatest achievement came with her early adoption of the "cyanotype", a simple photographic process that uses a photosensitive chemical solution to produce an electric-blue print. Her masterpiece Cyanotype Impressions, produced between 1843 and 1853, is one of the most beautiful and sought-after scientific books of the 19th century. The Linnean Society is privileged to have a copy in its keeping.

As part of its Linnean Lens events series, the Society's Librarian Will Beharrell held an online, "hands on" event with the Cyanotypes last August. A recording of that event is available online.

Cecilia Glaisher (1828–1892)

It would be unfair to mention Anna Atkins without also introducing Cecilia Glaisher, a fellow Kent native who helped do for ferns what Atkins did for algae.

Bree's fern from Glaisher's The British Ferns

Details of Glaisher's early life are scant, but her father, John Henry Belville, was an Assistant Astronomer at the Royal Observatory Greenwich, and her husband, James Glaisher, was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1849. It's likely Cecilia acquired her photographic skills with support from her husband.

Today she's best known for her work with The British Ferns: a planned project to create photographic impressions of British ferns for a scholarly audience. An initial tranche of 10 plates was produced, and eventually presented to the Linnean Society Library in 1855 (where they can be found to this day), but for unknown reasons the project was abandoned.

Still, Glaisher's work is now greatly prized for its delicacy and sophistication, and we can only imagine how magnificent the unfinished volumes might have been.

Sarah Anne Drake (1803–1857) and Augusta Withers (1792–1877)

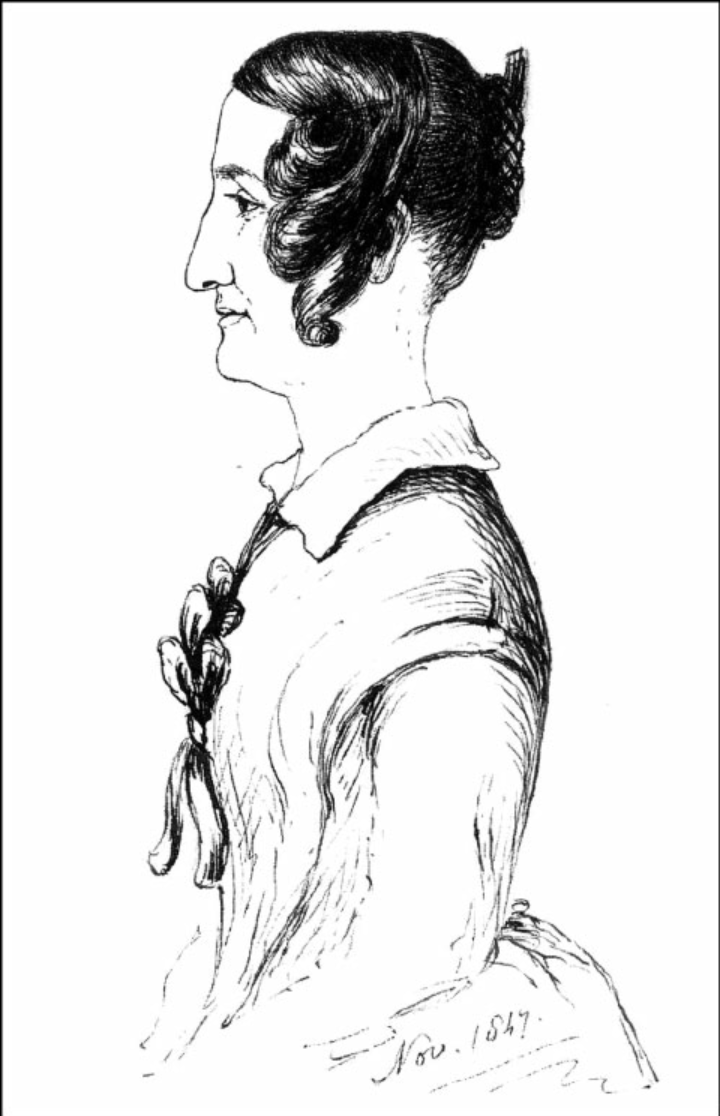

Sarah Anne Drake, in an 1847 sketch by either Sarah or Barbara Lindley

The botanical illustrator Sarah Anne Drake had close links with prominent Fellows of the Linnean Society, and collaborated with them on a number of projects. John Lindley, James Bateman, and Nathaniel Wallich all drew upon her astounding artistic skills. Born in the same area of Norfolk as Lindley, she clearly moved in a coterie of early-19th century East Anglian botanists that may have included our own James Edward Smith (born in Norwich in 1759, and founder of the Linnean Society in 1788).

Perhaps Drake's most spectacular work is to be found in James Bateman's Orchidaceae of Mexico and Guatemala (1837–1843); a gargantuan visual survey of South American orchids that has become legendary—if not downright infamous—for its vast size and expense. The Linnean Society is privileged to own a copy of this most ostentatious book, and it featured as our Treasure of the Month earlier this year.

Plate VII, Stanhopea tigrina, by Augusta Withers, from Bateman's Orchidaceae (1837–1843)

Drake's most prolific collaborator on the Orchidaceae was Augusta Withers, another woman with close Linnean Society links. Born in Gloucestershire, but based for most of her life in London, Withers worked with a succession of prominent botanists and nursery-keepers, including William Jackson Hooker, the first director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Probably the pinnacle of Wither's career came with her appointment as "Flower Painter in Ordinary" to Queen Adelaide in 1830, and later to Queen Victoria (the Linnean Society's Royal Patron).

Eliza Gleadall (c.1806–1887)

The popularity of Carl Linnaeus' classification system long outlived him, and enterprising botanists, scientific illustrators, and publishers continued to make effective use of this most accessible and reproducible of schemes long into the 19th century.

"The Mexican Tiger Flower": plate 17 from Eliza Gleadall's Beauties of Flora (1834)

One such was Eliza Gleadall, a Lincolnshire-born teacher turned botanical illustrator, whose sumptuous flower book, Beauties of Flora (1834), recorded the rare and exotic hothouse plants of local aristocrats in 40 intricate engravings. In the preparation of this volume she was mentored by Samuel Curtis—botanist, publisher, and Fellow of the Linnean Society—so she might "execute the style of the plates" so as to make "correct copies of nature".

Gleadall does not appear to have interacted with the Linnean Society directly—no correspondence from her survives in our archive, and no copy of her works grace our shelves—but she appears in the orbit of at least one of our Fellows, and her reputation endures in a rare and magnificent book.

In an overdue recognition of her achievements, Eliza Gleadall will be honoured with a blue plaque in Wakefield this International Women's Day.

Beatrix Potter (1866–1943)

Photograph of Beatrix Potter, aged 15, taken by her father

Beatrix Potter is famous around the world for her much-loved children's stories, but she was fêted in her own lifetime as an accomplished scientific watercolourist, conservationist, and mycologist.

Her dealings with the Linnean Society have been much discussed by scholars and biographers, and it is commonly alleged that the paper she submitted for reading at a Linnean Society meeting was rejected on account of her sex. This isn't true; the paper was in fact accepted to be read and discussed on 1 April 1897, but then withdrawn a week later by Potter herself before it could be printed. It is possible, as was common at the time, that the Society had requested alterations or corrections prior to publication, which for unknown reasons were never made.

Mycological illustration of the reproductive system of a fungus (Hygrocybe coccinea), by Beatrix Potter

Still, it is true that as a woman Beatrix Potter would not have been able to present a paper on equal terms of Fellowship with men, and the Society's Executive Secretary conceded in 1997 that she had been "treated scurvily" by the all-male scientific community of her day.

You can read more about Beatrix Potter, and her mycological work, in this article from our website, and also in this article by Prof. Roy Watling in The Linnean.

Who are your scientific heroines? Let us know the women who have influenced or inspired you in your life and career, and we'll collect together some of the suggestions in a forthcoming article.

You can email your suggestions to us at the Linnean Society (with the subject line "International Women's Day 2022").

Image Credits

Unless otherwise stated, all images © The Linnean Society of London, 2022.

Some images in the public domain have been reproduced courtesy of the following sources or institutions:

- Photographic portrait of Anna Atkins (1861) in the public domain, reproduced from the digital copy in Wikimedia Commons.

- Lithograph portrait of Elizabeth Blackwell in the public domain, reproduced from the digital copy courtesy of the National Library of Medicine Digital Collections (US).

- Sketch of Sarah Anne Drake in the public domain, reproduced from the digital copy in Wikimedia Commons.

- Plate VII, Stanhopea tigrina, by Augusta Withers, from Bateman's Orchidaceae (1837–1843) reproduced from the digitised copy at Biodiversity Heritage Library. Contributed by the Missouri Botanical Garden, Peter H. Raven Library.

- "The Mexican Tiger-Flower" (Eliza Gleadall, Beauties of Flora, 1834) image in the public domain reproduced from the digital copy courtesy of UW-Madison Libraries.

- Photographic portrait of Beatrix Potter in the public domain, reproduced from the digital copy in Wikimedia Commons.

- "Mycological illustration of the reproductive system of a fungus (Hygrocybe coccinea)", by Beatrix Potter and in the public domain, reproduced courtesy of the Armitt Museum and Library.

Further Reading

At least two of the women in this article also feature in the Linnean Society's new book L: 50 Objects, Stories & Discoveries from The Linnean Society of London, available for purchase from our online store.