'A Curious Herbal' as Material Witness

Hand printed books can tell a much more human story than today's machine-made ones. Janet Tyson discovers a few hidden among the pages of an 18th century book

Published on 10th January 2023

It’s not known how many copies were printed of 'A Curious Herbal', nor is it known how many still exist. However, more than 100 copies of the book produced by Elizabeth Blackwell (1699-1758?) have been located in institutional libraries in Britain, Western Europe, and the United States. Among them is the one held by the Linnean Society — presented as a gift in 1873 by the surgeon and naturalist William Tiffin Iliff (1798-1876). Elected a Fellow of the Linnean Society (FLS) in 1833, Iliff also sat on the council of the Medico-Botanical Society of London.

As Linnean Society librarian Will Beharrell has written, the Society’s copy of 'A Curious Herbal' possesses a number of distinctive characteristics. Most conspicuously, the title pages for both volumes were trimmed to the edges of their plate impressions, then pasted album-like on to larger leaves. It also is relatively rare for having uncoloured illustrations.

This essay addresses an aspect of the Linnean Society's copy’s title pages — their volume numbers — within the context of the above-noted survey of library holdings. Other pages also present noteworthy distinctions, but they are too numerous to consider here. Also addressed is a topic that has been persistently misrepresented for more than 250 years: Elizabeth Blackwell’s identity. Although not an aim of my survey, which concerned bibliography rather than biography, her birthdate and place, and father’s name were discovered in the course of that research and will be addressed first.

An Undiscovered Life

Up until very recently, Elizabeth has been identified as a native of Aberdeen, likely because that was the native city of her husband Alexander Blackwell (1709-1747). The earliest writings focused on Alexander, whose colourful life ended with his execution in Stockholm. Alexander’s misadventures were identified as the trigger for Elizabeth producing the 500 illustrations and 125 explanatory pages that constituted 'A Curious Herbal'. Eventually, interest in her outstripped that in her husband, but absence of information about Elizabeth led to biographical fabrications that still circulate today.

Last August (2022), my survey of Herbal copies took me to the Rubenstein Library at Duke University. From information found online, I knew that the copy they held was particularly fine — oversize and beautifully hand-coloured. What I didn’t know was that, out of the more than seventy copies I had thus far examined, it would be the only one to contain a preface, written by Elizabeth. In it, she identified her father as a decorative painter named Leonard Simpson.[1]

Research in other primary sources already had revealed that her uncle, Sir William Simpson, was prominent in the judiciary in London;[2] that her mother was Alice Simpson, who lived with Elizabeth in Chelsea, while Elizabeth worked on Herbal production;[3] and that Elizabeth Simpson, spinster of St Paul Covent Garden, and Alexander Blackwell were married in the exclusive chapel of Lincoln’s Inn.[4]

But Elizabeth’s birth date and place could not be known until her father’s identity was established. Her reference to Leonard Simpson and his occupation made it possible to find records for the Parish of St Mary Woolchurchhaw, which confirmed the birth and baptism of a daughter to Leonard Simpson, ‘Designer in Paintings’,[5]

and his wife. They lodged with a shoemaker in The Poultry, in the City of London and their child, Elizabeth, was born on 23 April 1699. As a girl and young woman, she loved to draw plants. As a married woman, she would draw and etch 500 pictures of medicinal plants to be compiled into a book called A Curious Herbal.

Each Copy, a Different Story

Both volumes of the Linnean Society's copy were published by John Nourse (c 1705-1780) in 1739. Elizabeth’s second publisher, Nourse was well-regarded for producing and selling books on science. The Herbal’s 1751 re-print also was published by Nourse and, after his death, the 1782 re-print was published under the name of his brother Charles. As Will Beharrell has written, the Linnean Society's copy's title imprints are unusual in that they were trimmed right to the edges of the plate impressions, and pasted on to other sheets of paper as though in albums. Another cut-out title page hasn’t been found, but one of three copies held by the Merz Library of the New York Botanical Gardens has a leaf with trimmed head pieces from the Censor’s and ‘Publick Recommendation’ pages pasted down.

The Linnean Society copy has other distinctive features that are not addressed, so that more attention can be given to the work’s title pages. Despite having been cut-and-pasted, this copy’s Nourse-imprinted title pages are paradigmatic — such that they diverge from so many other, erratically numbered title pages. Cleanly engraved Roman numerals for Linnean volumes one and two are situated precisely in the space that the Herbal’s first publisher, Samuel Harding (title pages dating 1737) reserved after the inscription ‘Vol: ’. That said, Harding’s title pages for volume one most often are in manuscript Roman I — in ink or in pencil — whilst the numeral for Harding’s volume two is an exquisite, engraved Arabic ‘2’.

The most eccentric treatment of volume references, however, comes when no number is given and the space is left blank. Such is the case with Nourse volume one at the Library Company of Philadelphia; both Nourse volumes at the Lindley Library in London; and a Nourse volume one held by the New York Botanical Garden.

Elizabeth Blackwell's parents were lodged with a shoemaker in The Poultry, in the City of London when Elizabeth was born on 23 April 1699. As a girl and young woman, she loved to draw plants. As a married woman, she would draw and etch 500 pictures of medicinal plants to be compiled into a book called A Curious Herbal.

And, although some pairs of Nourse’s title pages are as harmoniously numbered as the Linnean Society's, there are irregularities in plenty of those that were printed for him. Nourse inherited the plates that Harding had engraved, and the cleanest and most proactive means of dealing with the residue of his name, address, and publication date was to have those inscriptions thoroughly burnished out and re-engraved.

As indicated with respect to the Linnean copy, Nourse did a pukka job with those details, which are found at the bottom of each title page. But awkward hand-written Roman numerals for volumes one and / or two are found in copies in Amsterdam, Aberdeen, and Birmingham, among others. And what likely is the most intriguing means of marking volume one — accomplished by eradicating the second ‘I’ in ‘II’ — is seen on title pages in copies in Paris, at St Andrew’s University, at Wake Forest University in North Carolina, and at Royal Holloway, University of London.

In some instances, half of the numeral has been inadequately abraded, so that traces of original imprint linger like the ghost of a twin. In other instances, opaque white watercolour or bodycolour (the eighteenth-century equivalent of Liquid Paper or a Wite Out pen) was used.

But what can be learned from all of these bibliographical bits and bobs? The key point is that books printed by hand tell a much more human (flawed and imperfect, that is) story than do the machine-printed and bound books we see today, stacked in identical copies on tables at Waterstones. Vagaries in the Herbal’s title pages reflect Nourse’s eventual buy-out of Harding’s right to publish Blackwell’s book. Nourse, then, could use the plates that Harding had had engraved, and use illustrations, title pages, and other pages that Harding already had had printed. The details addressed above also show Nourse making do, when he evidently fell short of volume one title pages, and had to modify volume two title pages to fill the gap.

As a result, we can see that even a relatively prosperous publisher such as Nourse needed to practice thrift in terms of materials and production time. Quite apart, then, from A Curious Herbal’s testimonies to the virtues of traditional medicine, as communicated by its illustrations and accompanying explanations, its materiality communicates the eminently salient virtues of avoiding waste.

By Janet Stiles Tyson, the leading authority on Elizabeth Blackwell and 'A Curious Herbal'; she received her PhD in Early Modern history from Birkbeck, University of London in 2022.

References:

[1] See Blackwell preface in shelf mark QK99.A1 B544 1737 v. 1. Also see Stiles Tyson post: https://blogs.library.duke.edu/rubenstein/2022/11/14/a-curious-herbal/

[2] British Library Sloane MSS 4054 f 90. Letter recommending Blackwell, written by physician Alexander Stuart to Sir Hans Sloane.

[3] TNA, Court of Chancery, Six Clerks Office, Pleadings 1714-1758, doc C 11//1543/7. Alice Simpson deposition.

[4] ‘Records of the Honourable Society of Lincoln’s Inn: Chapel Registers’, https://archive.org/details/VOL218001893CHAPELREGISTERS/page/n595/mode/2up

[5] London Metropolitan Archives. Parchment register of the parish of St Mary Woolnoth, 1686-1726: LMA, P69/MRY15/A002/MS07636, and London Metropolitan Archives. Paper register of the parish of St Mary Woolnoth, 1695-1706: LMA, P69/MRY15/A/002/MSo7636.

Library Catalogue Record

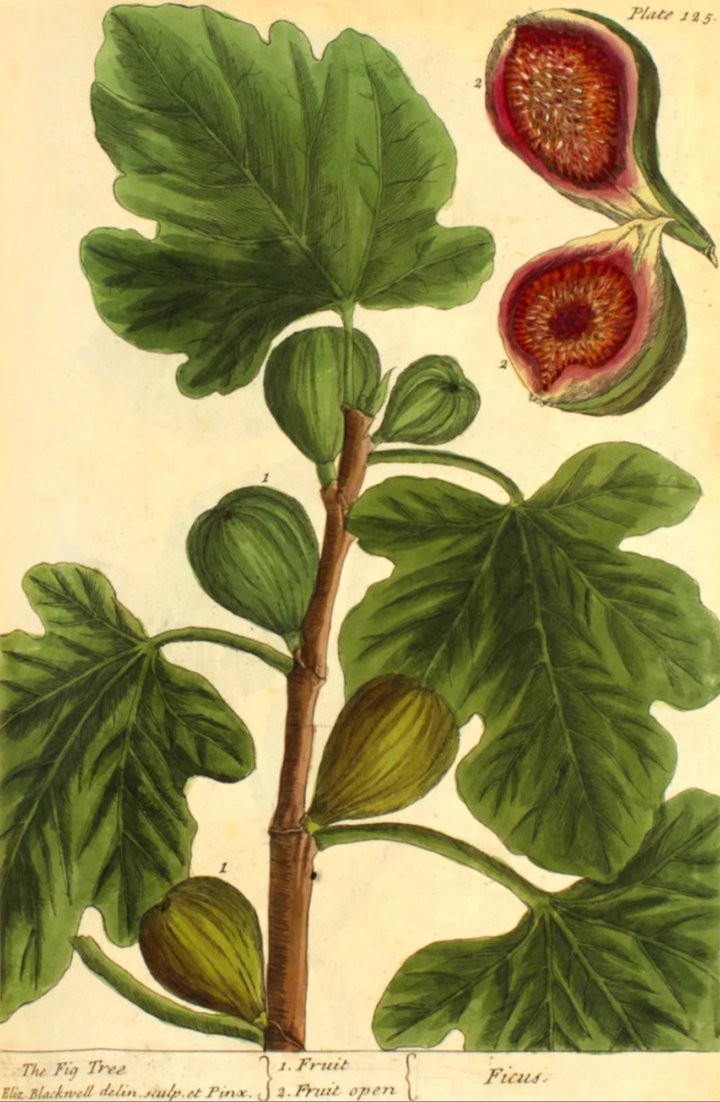

Blackwell, Elizabeth, active 1737. A curious herbal, : containing five hundred cuts, of the most useful plants, which are now used in the practice of physick. Engraved on folio copper plates, after drawings taken from the life. / by Elizabeth Blackwell. To which is added a short description of ye plants; and their common uses in physick. London: Printed for John Nourse at the Lamb without Temple Bar., MDCCXXXIX. [1739].

Item Reference: RF.739

View the online catalogue record

Minor corrections were made to this article on 3 June 2024.