An Insider's Tour of Wellclose Square: The Origin Story of the Wardian Case

Liz McGow, Archivist, leads us through Nathaniel Ward's half home-half laboratory in South London

Published on 3rd July 2023

The portrait of Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward (1791-1868) hangs on the walls of the Society’s Meeting Room and this illustrious Fellow is regularly mentioned in our tours due to his remarkable invention, the “Wardian case”.

![Portrait of Nathaniel B. Ward by John Prescott Knight [OP/W/3]](https://ca1-tls.edcdn.com/content/_720xAUTO_crop_center-center_none/1Ward_OPcropped.jpg)

For many years Ward, a physician and botanical enthusiast, had tried to grow plants at his home in Wellclose Square, East London, but the polluted air of the city, always thwarted his efforts. In 1829, quite by accident, Ward discovered that placing a plant inside an airtight container successfully protected it from any poisonous environments.

Further experimentation by Ward revealed that a sealed glass case could be used to create habitable conditions for plants when being transported for long periods of time, such as, on board a ship, without the risk of them dying from lack of water or exposure to elements such as rough winds and sea water. [1]

Much has been written about the details of Ward’s accidental discovery, as well as the far-reaching effects his invention had on the botanical world. [2]

This ranges from the mobility of global commodities, such as tea and coffee, as well as the tastes of Victorians who now had both access to exotic plants from abroad and the means to grow them in their own homes.

Within the Linnean Society archives, we hold correspondence of Ward (MS/325) as well as a number of scientific papers which Ward wrote, including one reporting the successful transportation of specimens of Musa Cavendishii on a voyage to Upolu in the Navigator Islands [Samoa] in his experimental construction (SP/1240).

Inspired by another item in our archive relating to Ward, the focus of this story is Ward’s home in East London, where he first stumbled upon his discovery.

A later addition to the archive, MS/715 consists of a small pen and ink sketch, with a large gold border, depicting an abundance of plants and some rocks.

Stored in a plain, brown envelope, the only information comes from a small, neatly typed label on the reverse of the sketch.

‘A corner of Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward’s conservatory in Welclose [sic] Square, by his third daughter, Miss Maria Ward.

Presented to the Society by the Misses Phipps Tiarks, of 82, West Hill, Sydenham, 11th July 1934.’

The stylistic nature of the picture, and the lack of colour, makes it hard to identify many of the plants for certain but it seems as though Ward was growing ferns and palms. In the background you can see upright lines which, presumably, are the bars of the glazed structure.

![Letter from Miss Eva Phipps Tiarks to the Linnean Society [Ref: DA/COL/2/1/16]](https://ca1-tls.edcdn.com/content/_720xAUTO_crop_center-center_none/6LetterfromEva.jpg)

Ongoing work on our Domestic Archive by Alex Milne, our Project Archivist, has uncovered material which puts an interesting twist on this item, as well as revealing the connection between the donor and Ward.

Miss Eva Phipps Tiarks (we learn in letters to the Society) was the god daughter of one of Ward’s daughters, Mrs Charlotte Elizabeth Ward (later Mrs Robert Braithwaite). In 1934 Eva contacted the Linnean Society offering to donate items inherited from her godmother, including:

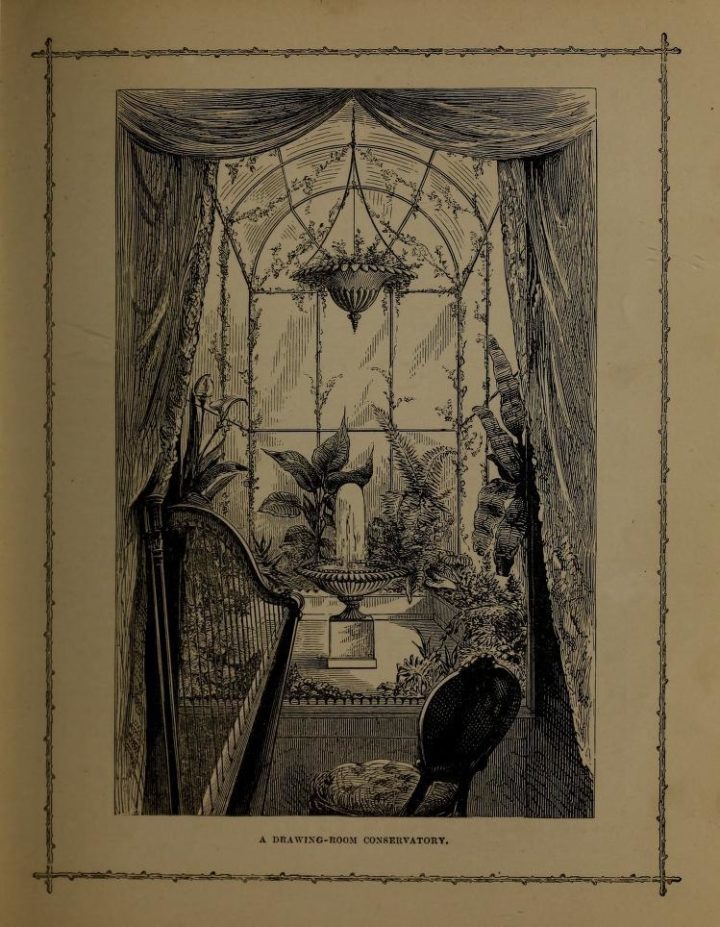

‘a very fine etching of plants in a corner of Mr Ward’s conservatory at Welclose [sic] Square. This etching was done by Miss Maria Ward who was a very talented amateur artist. And she told us that her father had formed this conservatory by enclosing, with glass, the whole balcony of their drawing-room at Welclose [sic] Square.’

So instead of the conservatory being a free-standing building outside in the garden, it has actually been created using the balcony of the drawing room. One suddenly feels all the more immersed in this tropical scene, especially when you realise that you are viewing it (as Maria the artist was) from inside the house.

Intrigued by the idea of a conservatory being created in such a way, I decided to look further into Ward’s home at Wellclose Square. The original property appears to be no longer standing but details can be found from other sources.

In 1842, Ward wrote a short publication entitled ‘On the growth of plants in closely glazed cases’ in which he attempted to explain the principles behind his design. This accessible, how-to guide, written while the author was still living at Wellclose Square, outlines a number of experiments Ward was conducting in his own home: numerous bottles, bell-glasses and structures (in glass and wood) had been placed in various locations around the house, including in different rooms, as well as outside stair-case windows, and even on the roof! He also experimented with cases in different positions of the house (e.g. Northern vs Southern aspect), as well as the use of natural vs artificial light and heat such as placing cases near to gas lamps.

Rev Shirley Hibberd in his wonderfully entitled publication, 'Rustic Adornments for Homes of Taste', first published in 1856, offered details to the discerning home owner on how one can improve the appearance of one's property, including the use of birds in cages and glass cases of plants. He devotes an entire chapter on 'Enclosed window gardens'. Therefore, clearly Ward was not alone in this practice, and it seems likely that he was an early proponent.

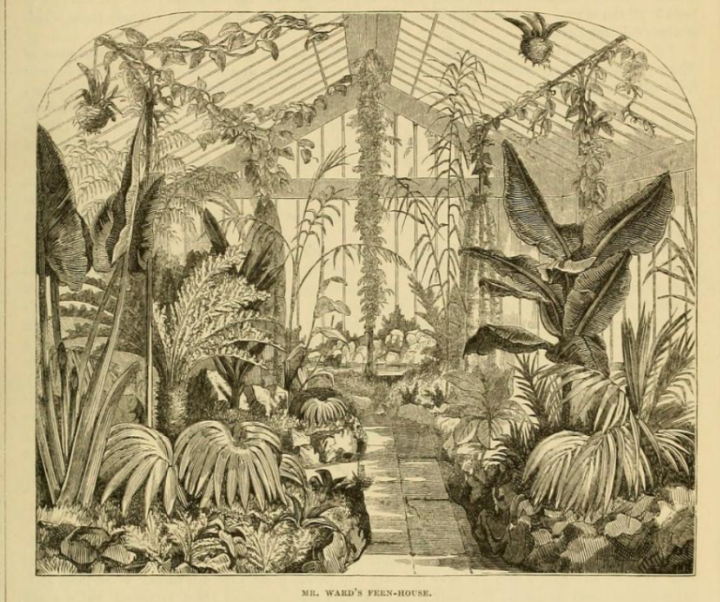

Ward went on to create a similar set up at his next home, Clapham Rise, in South London, and we hear more about this property in an article in The Gardener’s Magazine following a visit by the renowned author and garden designer, John Loudon. On his most recent construction, a large closed case in the garden, Ward explains that his aim was ‘to give a representation (in miniature of course) of a tropical forest, in which the plants were seen to be growing in something like a state of nature’.

Half home-half laboratory Ward seems to have used every available space around, outside and even on top of his various homes to further understand the principles behind his initial discovery. His publication, accompanied by the vivid sketch of the conservatory by his daughter, showing just one of the cases at Wellclose Square, provide a fascinating insight into Ward’s intriguing domestic arrangements. In the process of his experiments he must have created a peaceful, and also tropical, retreat from the noisy, polluted streets of London. The fact that Maria took the time to produce this elaborate drawing shows that the set-up clearly left an impression on her. One wonders what the rest of the family made of it!

Footnotes

[1] Ward was very familiar with the harsh realities of sea as, having expressed a desire of becoming a sailor, his father sent him, aged 13, to Jamaica to gain first hand experience on board ship. The trip had the desired effect as he abandoned his initial career plan and went on to study medicine. It was the same trip to Jamaica which sparked his passion for natural history having been overwhelmed by the beauty of the tropical vegetation and local sea life.

[2] For further details see an interesting blog by Katie Avis-Riordan from the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew.

Also watch this lecture by historian and curator Luke Keogh, who wrote 'The Wardian Case: How a Simple Box Moved Plants and Changed the World'.