Out of the Andes, Always Something New

How a new species of tropical butterfly eluded discovery by hiding in the snow

Published on 10th January 2025

Ex Andibus semper aliquid novi

As Pliny the Elder once said when he witnessed giraffes for the first time, Tomasz Pyrcz et al., authors of a recent paper published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, so too felt appropriate: “Out of Africa, always something new”. Though in this case we’re not talking about a long-necked giant but rather a delicate butterfly found flittering at almost 5,000 m above sea level…in the snow.

Whilst it’s not the first time a butterfly has been found in an extreme environment, this discovery marks the first time a tropical butterfly has been found to thrive in such conditions, completely disregarding what we thought we knew about this clade. The full paper can be found published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society.

Brrrr...illiant idea living up here?

As a general rule, as elevation increases, insect diversity decreases. Low air density, reduced oxygen, extreme temperatures, and gusty winds make flight an extremely risky (and energy-intensive) behaviour. The chances of freezing and desiccation increase exponentially, especially for those with delicate wings.

Of course, Mother Nature has found her ways around this. Cold-adapted species have developed physiological adaptations suited to extreme temperatures. Haemolymph, an insects’ equivalent of blood, contains antifreeze substances that lower their freezing temperature, increasing their frost tolerance as a result. If humans had this, you’d never need a coat again.

Similarly, other high-altitude butterflies found in Asia have behavioural adaptations to their environments. Their imagoes (the scientific name for an adult butterfly) are only active during summer, leaving their larvae/pupa to tackle winter conditions. Yet this adaptation is not possible in the Andes as seasons are less obvious; summers are drier, and winters are more humid with heavy snowfall.

High altitude butterflies are also physically different from their lower altitude relatives, with size a major factor. Much smaller than similar species, they’re typically white or silver in colour, acting as an effective means of thermoregulation (maintaining a constant body temperature) in icy conditions. What’s more, they fly quickly and low to the ground, often just passing through at 5,000 m rather than staying put. Yet here, the newly discovered species is different still, boasting large brown wings and slow gliding flight with a taste for snow. Not only is this novel for this region, it’s also completely unprecedented for butterflies in general!

Hunt for the wilder wings

Pyrcz and their co-workers began their mission in 2021, collecting live specimens from the Peruvian Andes using entomological nets (think the big nets you use in Animal Crossing). As butterflies are notoriously hard to sex without dissection, their next stage was to dissect the specimens’ genitalia, further aiding with the identification of a new species.

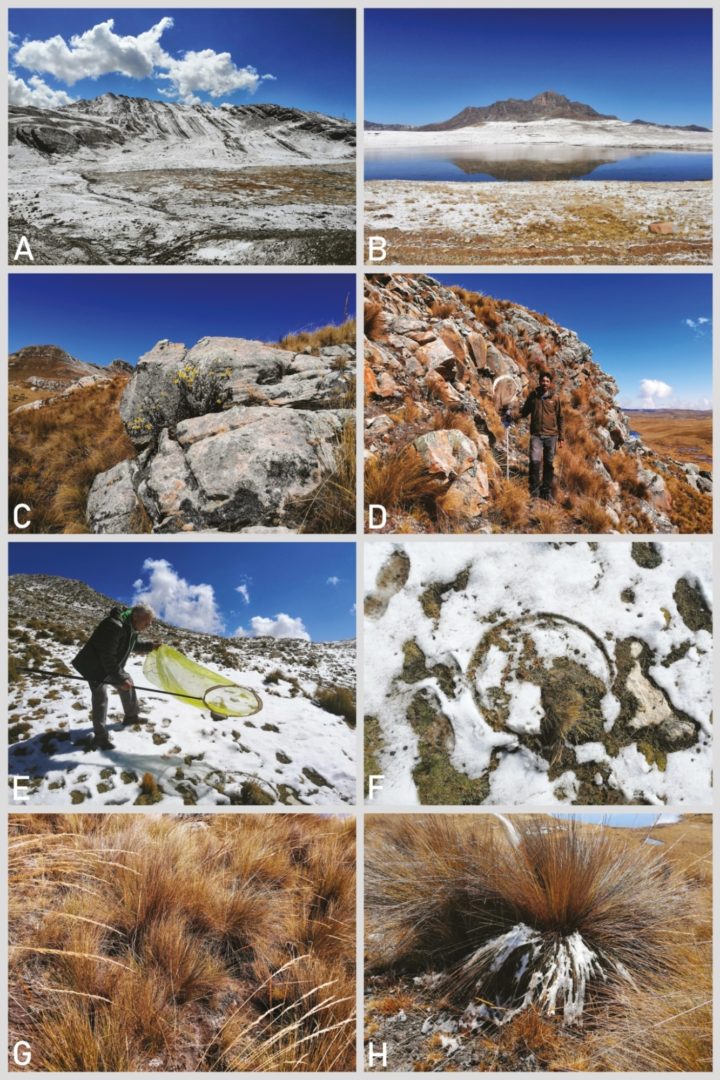

The habitat of Nivaliodes negrobueno, including the view from its type location Abra Negrobueno (A-C), researcher Jose Cerdeña on the steep slope where some individuals were found (D), Pierre Boyer pointing to the place where the first individual of N. negrobueno was collected (E), and the Stipa bunch grasses found in the habitat (G-H).

The discovery of a new species in this era is unusual, but to find one in such an unexpected place (somehow hidden ‘in plain sight’) is extraordinary. Lovingly named Nivaliodes negrobueno for the snow-white scales on their hind wings (Nival meaning ‘snowy’ in Latin) and the type-location of the first specimen (Abra Negro Bueno), it’s unique in several ways. It’s large and brown, with chestnut eyes and a hairy head, living in windswept rocky puna (a treeless plateau) at 4,750 m. Yes, you read that right, almost 5,000 m...

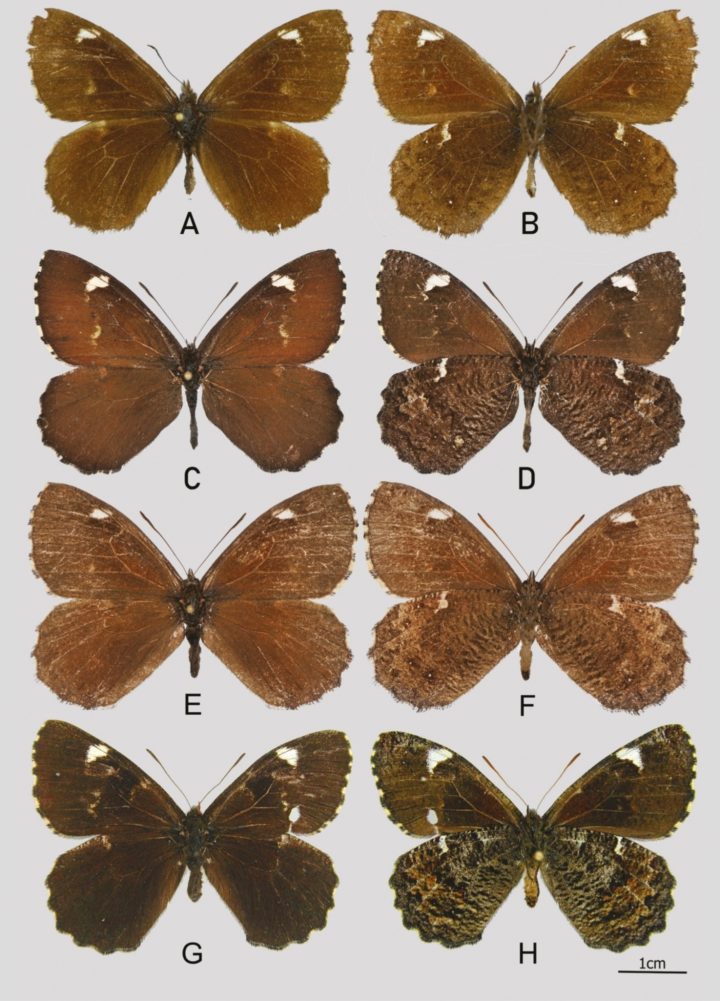

Adult male (A-D) and female (F-H) holotypes of the new species N. negrobueno, showing the variation between sexes. Snow white scales found on their wings help with thermoregulation. Their brown wings and relatively large size are unique to butterflies found at this elevation.

Butterflies of extreme weather stick together

While this species is brand new to science, they share a newly formed taxa with two similar species and are morphologically akin to their sister genus Pedaliodes (except in their genitalia). Therefore, the radiation of Nivaliodes was likely the result of climatic shifts, dispersal, and local adaptations, mirroring similar divergences in other groups of Lepidoptera.

Interestingly, sister status to Pherepedaliodes was unlikely, given no morphological similarities exist either externally or internally. Whilst Pherepedaliodes occur at mid elevations, and our new species is more associated with the timberline, the split likely happened relatively recently.

All three Nivaliodes species are closely related, consisting of our new N. negrobueno, as well as Nivaliodes puriq and Nivaliodes viracocha. Nevertheless, the occurrence of N. negrobueno at such extreme elevations compared to its closest relatives is extraordinary.

Adults of sister species N. puriq (A-D) and N. viracocha (E-H) showing their morphological similarity and near indistinction to the new species N. negrobueno.

It’s ecology baby

Over 400 species of the megadiverse Pedaliodes clade are found in montane habitats, most of which are strongly associated with their host plant, Chusquea bamboo. Yet only a smattering of species have been found above 4,000 m, including Punapedaliodes flavopunctata, the only puna specialist in the Central Andes and crowned “highest-flying species” within this clade. Reaching a maximum elevation of 4,200 m, this is 500–600 m lower than N. negrobueno! Looks like we have a new champion.

What’s even more astounding is that the temperature of dry air drops by about one degree every 100 m at extreme elevations, meaning that at the staggering 4,750 m the mean air temperature is 7–8 degrees cooler (oC). Paired with average day temperatures reaching a maximum of 18 oC and minimum of -20 oC, daily amplitudes can vary up to 40 oC! No other high-altitude species in central Asia or the Arctic are subject to such extremes.

Map of the Peruvian Andes showing the known locations of each species of Nivaliodes.

Though no oviposition was observed this time around, the only available Poaceae were Stipa and Pappostipa bunch grasses, with the nearest bamboo located 100 km away. Despite offering similar biochemical compounds, the switch from bamboo to grass is a rare evolutionary process among satyrid butterflies. They are, however, host plants for other high-altitude species, with the main restricting factor being the type of environment in which Poaceae are found. The only other grass-feeding representative of Pedaliodes is the aforementioned P. flavopunctata, yet this species is rarely found above 4,000 m. Pyrcz et al., hypothesise that selection of micro-habitats is therefore the main difference between these species.

Adults of N. negrobueno fly slowly over sharp rocks and ridges, often disappearing amongst the rocks themselves rather than flying among grasses. This is likely related to thermoregulation, with individuals taking advantage of and basking on dark rocks heated by the sun. However, researchers also saw these butterflies settling directly on the snow, something unprecedented in Andean butterflies! Whilst snow is known to form an insulating cover, this behaviour is so novel that it requires further investigation.

In conclusion

How have such large and conspicuous butterflies eluded scientific discovery or attention for so long? At this stage, there is still an extensive lack of research on this wonderful new species. However, Pyrcz et al., made it clear that their initial aim is to simply highlight the mere existence of the species, and briefly discuss its habitat and behaviour. The conditions at almost 5,000 m in the central Andes are harsh and unforgiving, both for the focal species and the researchers themselves. As such, further investigation requires a meticulously planned and well executed long-term study. What’s clear, however, is how unlikely it is to find a ‘tropical’ butterfly capable of living up here. Therefore, the key takeaway is to highlight that there is still so much to discover on our blue planet, even though it may not feel that way.

Ultimately, we at the Linnean Society must agree with the authors of this paper and indeed Pliny the Elder – Ex Andibus semper aliquid novi – new species really are all around.

Blog Editor

Compiled and edited by Georgia Cowie, Journal Officer (Linnean Society) © The Linnean Society